Welcome to Carnivalesque #104! There's been all sorts of fascinating research being posted on the blogosphere, so let's take a look at what my fellow historians have been up to recently!

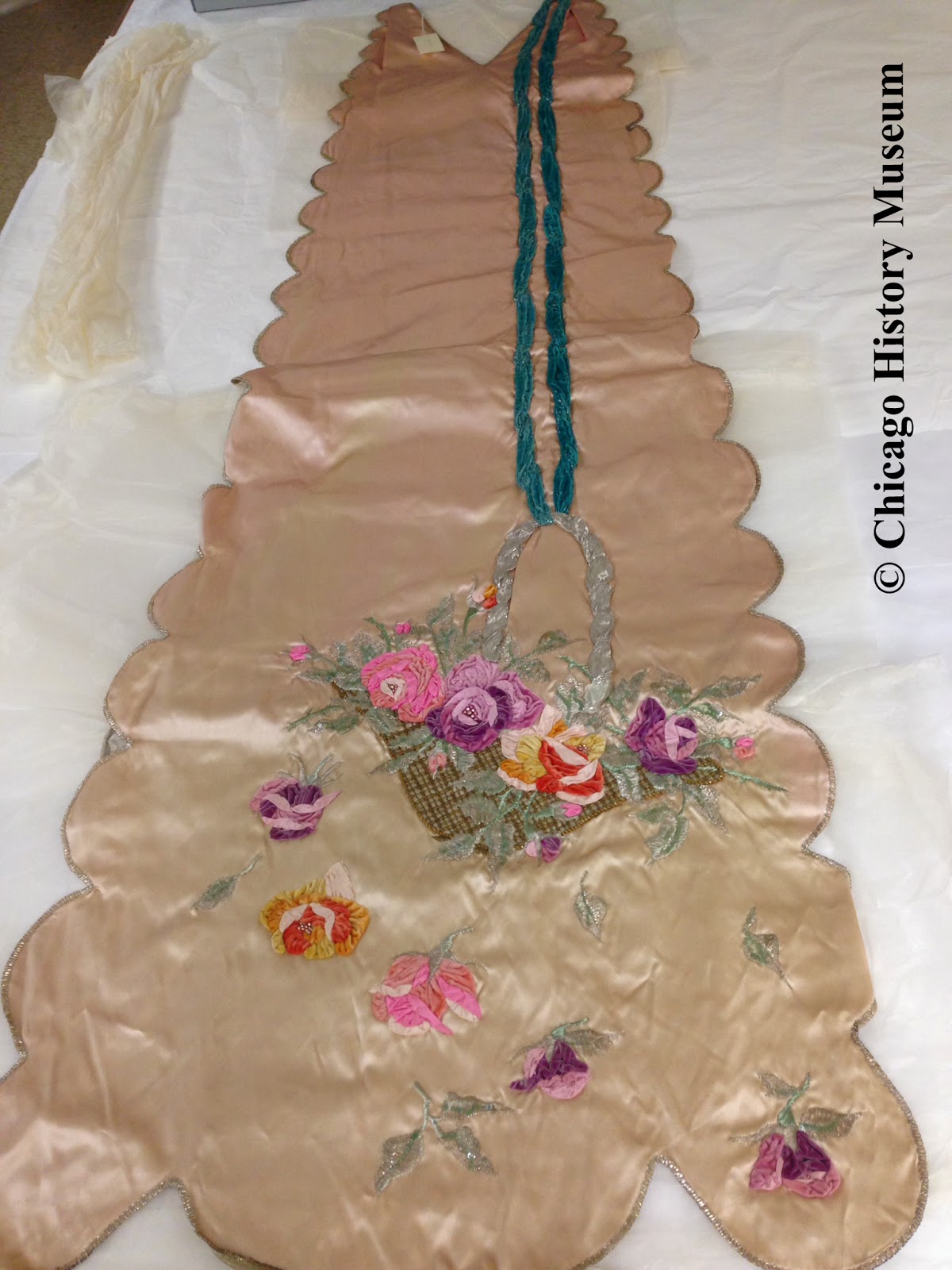

To start with some fashion history, the always wonderful

Two Nerdy History Girls have been exploring just how those giant 1770s hairstyles were created. In

Part 1 of this series they discuss a bit of the background of this hairstyle while busting some myths in the process.

Part 2 takes a closer look at how Abby Cox and Sarah Woodyard, the mantua-maker's apprentices at the Margaret Hunter shop in Colonial Williamsburg, have been recreating these large styles themselves using period techniques.

Over on

The Duchess of Devonshire's Gossip Guide to the Eighteenth Century, Heather Carroll tells us all about the fascinating

Eglantine, Lady Wallace in her Tart of the Week feature. Eglantine, known as Betty, was a bit of a wild child and had many adventures during her life, including dressing as a man to watch a debate in the House of Commons and at one point being accused of espionage. I suspect Betty was a very fun person to hang out with.

Turning over to some books and manuscripts, guest blogger Julie Park discusses

Interiority and Jane Porter's pocket diary at

The Collation. Pocket diaries provide a world of information about 18th century life, and in this post Park looks at one from 1796 which belonged to Jane Porter, the first bestselling female author of historical fiction who wrote under her own name. In this fascinating post, Park explores how Jane Porter literally went outside the lines in her use of her diary, concluding that "Porter appropriates and repurposes the spaces of the diary to accommodate the vicissitudes of individual experience."

Earlier personal writing is explored in the post

"My Well-Beloved Valentine", as

Lucy Allen takes a look at the 15th century love letters of Margery Brews. Fun Fact: These letters contain the first recorded English use of the word Valentine as a synonym for lover. In this romantic post, Allen discusses how Margery Brews created a more personal language than that traditionally used between couples and started a tradition that continues to this day.

And in a final manuscript themed blog post, Jenny Weston at

Medieval Fragments discusses

Medieval Family Trees, exploring how medieval families documented their history and achievements in beautiful artistic detail.

Taking a break for some fun and games, Mike Rendell at

The Georgian Gentleman takes a brief look at the history of the

yo-yo and how, in the late 18th century, it had a brief period of popularity as one of

the fashion accessories of the day.

And for some more active sports, Mike A. Zuber reports on

early modern football at

Praeludia Microcosmica. In this post Zuber links to some fascinating research about early modern football, noting that violence within the sport has a long history. Some games even led to death!

If you happen to be an ancient Babylonian suffering from epilepsy, Strahil V. Panayotov discusses how a doctor may have used

fumigation to cure you at

The Recipes Project. Panayotov writes, "Through fumigation the Babylonian medical practitioner could heal different illnesses: depression, epilepsy, troubles with the ears and the eyes, or even hemorrhoids." As the post goes on to reveal, the ingredients used to create this healing smoke could sometimes be a little odd. For epilepsy, the main ingrediant was parts of the head of a dead young male goat!

For those who enjoy tales of pirates, head over to

English Legal History where Rebecca Simon discusses

Pirate Executions in Early Modern London. Unlike many tales of the high seas, Simon's post explores the deadly fate of pirates who did not escape with their booty, and were instead taken to the Execution Dock and hung by the neck. In a particularly cruel twist, the nooses used for pirates were shorter than normal, meaning that a pirate's neck would not break as they dropped, causing them to die slowly of asphyxiation.

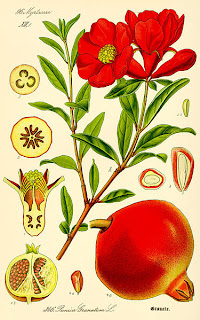

If all this fascinating reading has gotten you a bit hungry, why not head over to

Early British and American Public Gardens and Grounds where Barbara Wells Sarudy looks at

hunting, fowling, and shooting in 18th century America and Britain.

After all that meat you'll want a good drink, so head over to

The Many-Headed Monster where Mark Hailwood gives his

"Marooned on an Island" reading list all about the history of drinking. It is sure to fulfill all of your alcoholic history needs!

If all that food and drink has given you a bit of a stomach ache, then perhaps you should go to

Les Leftovers where Jim Chevallier discusses

shifts in fasting in medieval France. This detailed post considers what foods were and were not allowed on fasting days, when fasting days took place, and how all of this changed over time.

And that's all for this edition of Carnivalesque. I hope you have enjoyed exploring all of the amazing history that is available online as much as I have. Be sure to join us in September for Carnivalesque 105 at

Meshalim/Amthal/Exiemplos: Notes from the Life of a Medievalist.