Any visitor to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City should stop by Gallery 599 on their tour of the museum. It's a small gallery, to get there you simply descend a small flight of stairs tucked away in the back corner of one of the large medieval galleries. Gallery 599 is located by the door to the Ratti Textile Center, which houses all of the textiles in The Met's collections. A rotating exhibition showcasing small samplings of The Met's textiles is featured in the display cases surrounding the door to the Ratti Textile Center. It's a quick pitstop on your tour of the museum and always well worth a visit as you get to see some rarely viewed textile treasures.

Currently on view in Gallery 599, from now until July 17th, is Elaborate Embroidery: Fabrics for Menswear Before 1815. As explained in the press release, "This installation features lengths of fabric for an unmade man's suit and waistcoat, as well as a selection of embroidery samples for fashionable menswear made between about 1760 and 1815."

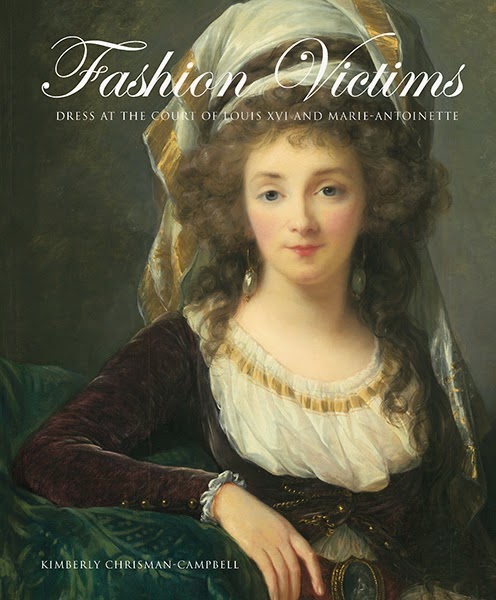

While I was in graduate school I was lucky enough to intern in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at The Met, where I worked with a number of textiles housed in the Ratti Textile Center. This included about 99% of the embroidery samples in The Met's collection. There are hundreds and hundreds of them, and most are quite small and are rarely exhibited. So I was quite pleased to see that some are getting their moment in the spotlight in this small exhibition. Including the sample pictured above, which dates to 1800-1815 (Fun Fact: A picture I took of this sample is currently the background on my phone).

Just from this picture alone, you can see that this is a truly spectacular piece of craftsmanship. The detailed embroidery renders exquisitely detailed flowers as the main motif, and the white border features tiny and meticulous stitches which resemble lace. But just a picture doesn't tell the full story of this textile.

Look closely at the textile on which the embroidery is done (click the image for a bigger size if you need to). The pattern is made from three colors: a deep purple background surrounding flowers of orange and a lighter purple. What's difficult to see in the picture is that the deep purple background is actually a rich silk velvet. The flowers have been created while the textile was still on the loom. As it was being woven, small sections were woven without any pile (pile is what makes velvet fuzzy), revealing the base fabric underneath. This type of velvet is called voided velvet. The weave of this textile is incredibly complex, and clearly took a great deal of skill to manufacture. And on top of what is already an extraordinary piece of work, the detailed embroidery is added.

Note the dimensionality this mix of textures adds. The lustrous silk embroidery seems to float over the matte velvet. And the soft texture of the velvet contrasts with the slightly ridged pattern of the weave underneath, making the small orange and purple flower shapes pop. I have never run my fingers over this textile, but I imagine the mix of textures would be interesting to the touch as well.

I don't know if a full suit was ever created based on the design featured in this sample (If it had it would have been extremely expensive and luxurious!). Fortunately for all of us, at least this small sample has survived. It, and others like it, show us not only the luxury of menswear in the 18th and early 19th centuries, but also the extraordinary talent, creativity, and ingenuity of textile manufacturers in history. Many of their names are not known today, but their work lives on and is honored through the study and exhibiting of textiles such as these.

|

| Embroidery sample for a man's suit, 1800–1815. French. Silk embroidery on silk velvet; L. 13 1/4 x W. 11 1/8 in. (33.7 x 28.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The United Piece Dye Works, 1936 (36.90.15) |

Currently on view in Gallery 599, from now until July 17th, is Elaborate Embroidery: Fabrics for Menswear Before 1815. As explained in the press release, "This installation features lengths of fabric for an unmade man's suit and waistcoat, as well as a selection of embroidery samples for fashionable menswear made between about 1760 and 1815."

While I was in graduate school I was lucky enough to intern in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at The Met, where I worked with a number of textiles housed in the Ratti Textile Center. This included about 99% of the embroidery samples in The Met's collection. There are hundreds and hundreds of them, and most are quite small and are rarely exhibited. So I was quite pleased to see that some are getting their moment in the spotlight in this small exhibition. Including the sample pictured above, which dates to 1800-1815 (Fun Fact: A picture I took of this sample is currently the background on my phone).

Just from this picture alone, you can see that this is a truly spectacular piece of craftsmanship. The detailed embroidery renders exquisitely detailed flowers as the main motif, and the white border features tiny and meticulous stitches which resemble lace. But just a picture doesn't tell the full story of this textile.

| Embroidery sample for a man's suit, 1800–1815. French. Silk embroidery on silk velvet; L. 13 1/4 x W. 11 1/8 in. (33.7 x 28.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The United Piece Dye Works, 1936 (36.90.15). Photo by Katy Werlin. |

Look closely at the textile on which the embroidery is done (click the image for a bigger size if you need to). The pattern is made from three colors: a deep purple background surrounding flowers of orange and a lighter purple. What's difficult to see in the picture is that the deep purple background is actually a rich silk velvet. The flowers have been created while the textile was still on the loom. As it was being woven, small sections were woven without any pile (pile is what makes velvet fuzzy), revealing the base fabric underneath. This type of velvet is called voided velvet. The weave of this textile is incredibly complex, and clearly took a great deal of skill to manufacture. And on top of what is already an extraordinary piece of work, the detailed embroidery is added.

Note the dimensionality this mix of textures adds. The lustrous silk embroidery seems to float over the matte velvet. And the soft texture of the velvet contrasts with the slightly ridged pattern of the weave underneath, making the small orange and purple flower shapes pop. I have never run my fingers over this textile, but I imagine the mix of textures would be interesting to the touch as well.

I don't know if a full suit was ever created based on the design featured in this sample (If it had it would have been extremely expensive and luxurious!). Fortunately for all of us, at least this small sample has survived. It, and others like it, show us not only the luxury of menswear in the 18th and early 19th centuries, but also the extraordinary talent, creativity, and ingenuity of textile manufacturers in history. Many of their names are not known today, but their work lives on and is honored through the study and exhibiting of textiles such as these.